Listen up, animal lovers; this one is for you…

If you ever find yourself asking, “Should I attempt mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on this baby rabbit my cat brought in?” The answer should be a firm “no”.

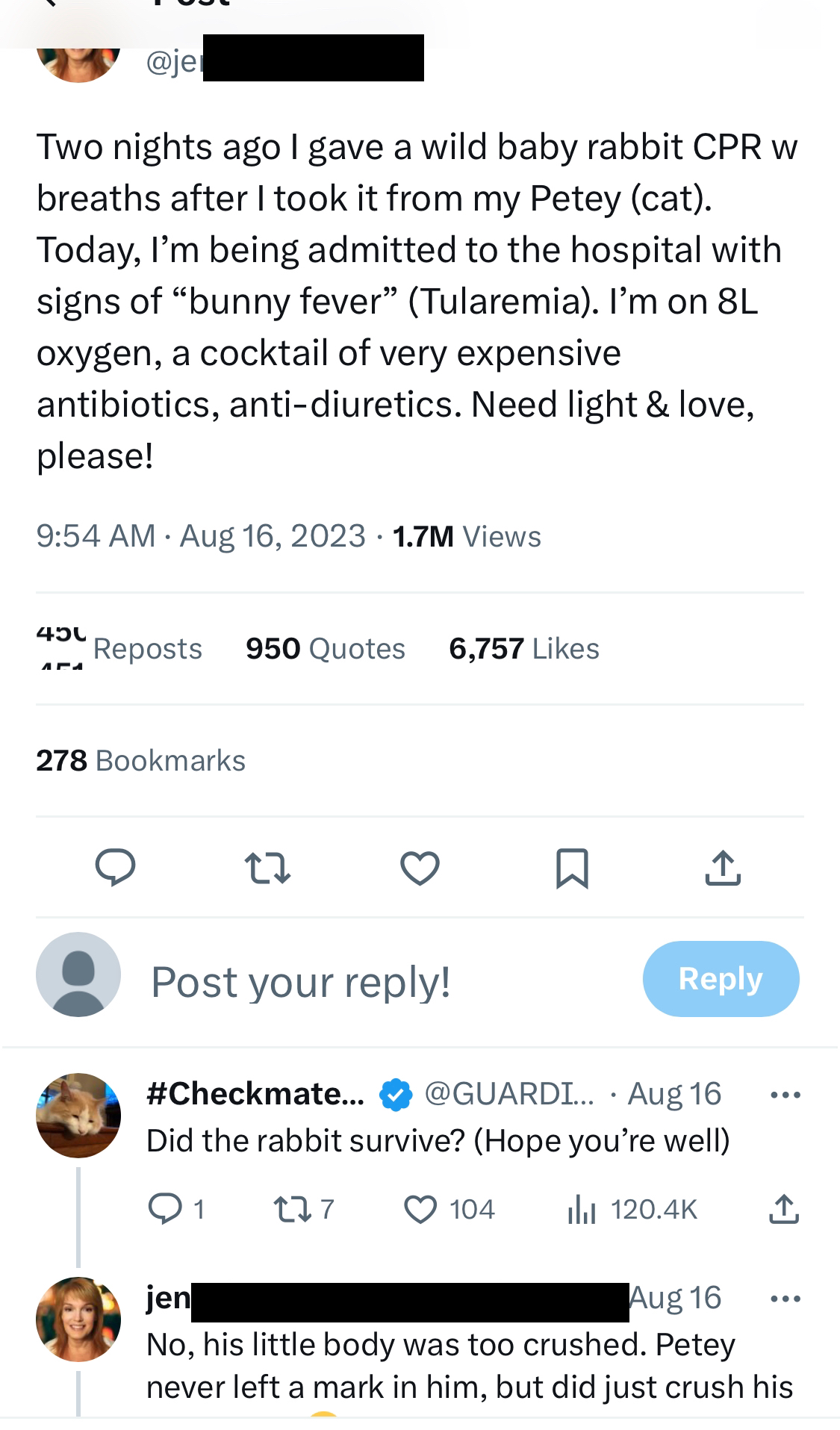

An X (formerly known as Twitter) user recently posted that she was about to be admitted to hospital after contracting Tularemia (rabbit fever) in a failed bid to revive a wild rabbit.

Some may describe the love we have for our furry friends as infectious. Of course, we don’t mean it in a literal sense; we simply cherish our pets.

However, when this love leads to emergency hospital admissions, we may need to question where to draw the line. So, before you decide to give the kiss of life to a wild animal in distress, here is something you might want to consider.

Zoonotic Diseases

A zoonotic disease is an infection transmitted from humans to animals or visa-versa. Experts describe these agents as ‘jumping’ from one species to another. These harmful particles may be bacterial, viral, or parasitic.1 These bugs can hitch a ride from their body (or lips) to your mouth, eyes, or broken skin.

Thankfully, our immune system has built up barriers to fight against these foreign invaders. When an infectious disease hops species, its symptoms can be extremely serious. The new host is not adapted to tackling this pathogen and will likely be hit hard by an intense immune reaction.

This reaction can have deadly consequences for the recipient. How about trying a kiss from a rose, rather than a rabbit?

Rabbit Fever

Rabbit fever is caused by a bacteria called Francisella tularensis.3

While we usually pick up the bug from rabbits, don’t let the name fool you- humans can also catch this disease from beavers, sheep, and mice.2 On average, 200 confirmed cases per year occur in the United States.4

Although rare, its symptoms are severe and can affect the skin, lungs, eyes, and lymph nodes, including:

- Sudden fever.

- Joint pain.

- Dry cough.

- Painful lymph nodes.

- Weakness.

- Skin Ulcers.

- Inflamed eyes.

- Chills.

- Pneumonia.

- Respiratory failure.

If not treated promptly, cases may be fatal. Healthcare professionals diagnose rabbit fever by a blood or saliva test that screens for the bacteria. If confirmed, patients will take a course of antibiotics for two or more weeks until the infection clears.3

Animal Encounter

Close contact with critters can expose you to many zoonotic infections.

Rabies

One of the most well-known is rabies. Rabies is usually spread through animal bites.

This is a deadly viral infection with symptoms including seizures, hallucinations, and paralysis.

Humans have a roughly 20-90 days-long incubation period before symptoms will set in. If you get treatment during this period, you have a good chance of survival. Doctors will give you a post-exposure vaccination capable of curbing the infection.

If you have been bitten by a wild animal, even a nip from a bat, go to your doctor and ask for advice. Luckily, this vaccine is also preventative so make sure you ask for it if there’s a chance you will be dancing with wolves!5

Flu

As the name suggests, bird flu is a type of influenza (the flu virus) that usually only affects birds. If a human catches unfamiliar bird flu, the symptoms can be more severe than human flu. It’s spread by close contact with their droppings or through the slaughter or butchering of infected birds.

Practicing good hygiene and avoiding uncooked poultry can save you a trip to the doctor with this zoonotic disease.6

Similarly, swine flu is a version of the flu virus that pigs carry. Humans can contract it through close contact with infected pigs. Human cases are common enough that it is included in the annual flu vaccination.7

Foot and Mouth

The highly contagious foot-and-mouth disease is a zoonotic disease mainly affecting children and farm animals such as cows, sheep, and goats. The infection spreads through contact with infected animals or virus-exposed surfaces.

Vaccination in animals and good hygiene practices in humans can spare you from the painful blister-like lesions, fever, and rash associated with this disease.8

Corona viruses

Corona viruses such as SARS, MERS and Covid-19 start off a routine sniffle in animals living their life in nature.

But if we are unlucky enough to get close enough to a coughing camel or a SARS-loaded sneeze from a raccoon dog, the result can be a serious case of acute respiratory disease.

Ebola

Another example of a viral zoonotic disease is the Ebola virus. This viral infection gained widespread attention in 2014 due to its sudden and rampant outbreak in West Africa. It earned the title of a zoonotic disease for its effect on both human and non-human (monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas) primates alike.

Compared to rabbit fever, the Ebola virus is far more deadly. Its symptoms include skin rashes, diarrhoea, and unusual bleeding or bruising. Measures such as contact tracing, sterilization, and vaccination programs helped curb the outbreak and bring an end to the deadly outbreak.9

Monkeypox

The most recent monkeypox outbreak sprouted in early May 2022, just as COVID-19 cases appeared to wind down in numbers and severity. Online accounts by infected individuals warned of intense skin rashes and lesions, accompanied by low energy and swollen lymph nodes.

Although this virus spreads between humans through close contact, the disease also infects monkeys, squirrels, and rats.10

Why are we hearing about zoonosis more?

Experts have warned against the harmful farming practices and habit destruction responsible for uprooting these wild animals and causing their unnatural integration into our communities.

Looking at infection trends, it appears that the number of zoonotic diseases is growing, and so too is the threat of another viral pandemic.11

With that, I hope this article has strongly cautioned anyone against resuscitating a wild animal in the near future. Instead, we should probably stick to mouth-to-human mouth rather than mouth-to-mouse!

References

- Zoonotic Diseases (2021) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html (Accessed: 09 September 2023).

- Foley, J.E. (2023) Tularemia (rabbit fever) in dogs – dog owners, MSD Veterinary Manual. Available at: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/dog-owners/disorders-affecting-multiple-body-systems-of-dogs/tularemia-rabbit-fever-in-dogs (Accessed: 09 September 2023).

- CDC Tularemia (2018) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/tularemia/faq.asp (Accessed: 09 September 2023).

- City of Toronto (2017) Tularemia (rabbit fever) fact sheet, City of Toronto. Available at: https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/health-wellness-care/diseases-medications-vaccines/tularemia-rabbit-fever-fact-sheet/ (Accessed: 09 September 2023).

- Rabies (no date) World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies (Accessed: 24 September 2023).

- Information on bird flu (2023) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/index.htm (Accessed: 24 September 2023).

- Ma W. Swine Influenza Virus: Current Status and Challenge. Virus Res. 2020 Oct 15; 288: 198118

- Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (no date) https://www.cdc.gov/hand-foot-mouth/index.html (Accessed: 24 September 2023).

- Ebola virus disease (no date) World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebola-virus-disease (Accessed: 24 September 2023).

- Mpox (monkeypox) (no date) World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox (Accessed: 24 September 2023).

- Barbier, E.B. (2021) ‘Habitat loss and the risk of disease outbreak’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 108, p. 102451. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102451.